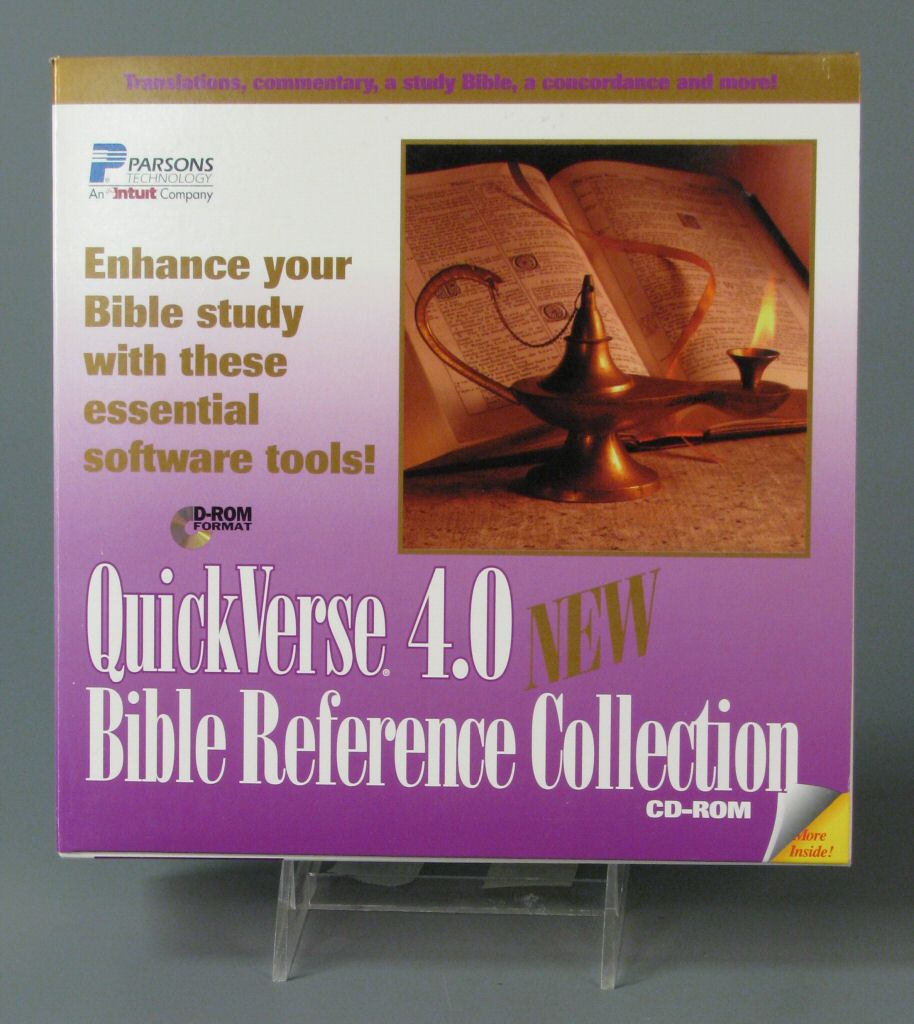

In 1990, I purchased a Bible software program for my first computer. It was QuickVerse 1.0. QuickVerse became a close companion in my personal Bible study for the next 15-years. I recently ran across Craig Rairdin on Facebook. Craig is the creator of QuickVerse, and the subsequent founder & developer of Pocket-Bible, marketed through Laridian. Craig was kind enough to give us this interview. This is part one.

Hi Craig, thanks for granting us this interview.

No problem.

Give us a quick timeline to help our readers connect the history of QuickVerse.

- I graduated in December 1981 and started working at Rockwell in January, 1982.

- I started working on the program that would become QuickVerse from home in late 1987 while working at Rockwell.

- I interviewed with Bob Parsons in the Fall of 1987, but he didn’t have any openings.

- I completed my Bible program in the Fall of 1988 and showed it to Bob.

- I left Rockwell to join Parsons Technology in November, 1988, as Director, Church Software Division.

- I was promoted to Vice President of Parsons Technology in 1990-91.

Where did you grow up?

I was born and raised in Cedar Rapids, IA and still live there (actually right next door in Marion, IA). I went to school at the University of Iowa just 30 miles south.

Was faith always part of your life?

Engagement picture in 1981.

I grew up going to church, but not one that preached the Gospel. I first heard the Gospel as part of a “lay witness weekend” where the church brought in people from around the state who had had a salvation experience to tell people in the church how to be saved – because of course there was nobody already in the church who was doing that. Very bizarre when I look back on it.

I accepted Jesus Christ during my junior year in college and immediately connected with a campus ministry at the University of Iowa, through which I met my wife.

How did you come up with the idea of QuickVerse?

Back in the late 80’s I got my first computer and was browsing through a software catalog when I found a set of about 10 disks containing the KJV Bible on sale for $50. It occurred to me that I could write a little program that accessed the Bible and would let me quickly go to a verse or search for a word or phrase. I originally wrote it with the idea that I would give a copy to my pastor and he and I would use it for Bible study. I wasn’t thinking about selling it when I first started in on it.

How did you choose the name?

The program was originally called “Logos Bible Processor”, which was kind of a take-off on “word” processing. I sold it under that name for several months. When I took the program to Parsons Technology in 1988, we decided it needed a better name – something that wasn’t so esoteric. We talked about names like “Sword’s Edge”, because the program was “quick and powerful," That led us to names that involved “quick”, like “Quick Search”, “Quick Bible”, and “Quick Word”. I think Bob Parsons actually came up with “QuickVerse." I didn’t like it at first, but looking back on it, it’s a great name.

Tell us about your relationship with Bob Parsons. Then and now.

I met Bob in 1987. He was an accountant for a leasing company who wrote a personal financial management program called MoneyCounts for MS-DOS. He lived across the street from a friend of mine. My friend introduced me to MoneyCounts, which I started using at home and at my church, where I was treasurer.

When I met Bob in the Fall of 1987, he had just left his full-time job to devote his full attention to MoneyCounts. I had been working as a programmer at Rockwell International for about six years and was looking for a new challenge, so I contacted him to see if he was looking for programmers. He invited me to come interview. I felt like we “connected” but he really wasn’t looking to hire anyone. He commented that he had just hired the best programmer he could afford – himself.

We talked a lot about his idea of creating really great software then selling it super-cheap so that it was an impulse buy. He was selling MoneyCounts for $12 at the time. He would take out full-page, full-color ads in major computer magazines, which made it look like he was a big company, but in reality it was just Bob and his wife Martha manning the phones.

After I wrote my Bible program and started selling it from my home, I got ahold of Bob to see if I could rent a mailing list of his MoneyCounts customers. I thought we could go through the list and grab the ones that looked like churches. Bob invited me to his office, which was in a real office building now and not just in his basement. Bob pointed out that churches were the largest type of small business in the US, and that he wanted to get MoneyCounts into more churches.

One thing led to another and I ended up going to work for Bob. He licensed my Bible program to sell as QuickVerse. He hired me to be director of a new division of his company, the Church Software Division. He gave me a two-pronged mission: To develop and market QuickVerse, and then figure out how to sell MoneyCounts to QuickVerse users and to the churches they attended. I suggested some feature enhancements based on my own experience using MoneyCounts at my church, and suggested we write a church management program to augment MoneyCounts with membership management and contribution tracking.

Bob was a high-energy entrepreneur. He had a way of immediately finding the weaknesses in your plans and forcing you back to the drawing board to come up with something better. He made decisions and changed directions quickly when he felt there was a shorter path to profitability. Not everyone could thrive in that kind of environment, but for those of us who did, the work was very rewarding and exciting. I learned a lot about business in the six or eight years I worked for Bob, and often hear his voice in my head when I’m facing a tough decision.

After selling Parsons Technology to Intuit in 1994, Bob phased out his involvement with the company and eventually started a Web hosting company called Jomax Technologies. When I started working on the program that would become PocketBible in 1998, I contacted Bob to have Jomax host our website and write our e-commerce system. The code they wrote for us in 1998 was in active use at our site until 2014, when I finally re-wrote it.

Jomax eventually turned into GoDaddy, which is the company most people recognize Bob from. Laridian does a little business with GoDaddy, but our website has outgrown them and most of the people we knew there (including Bob) have moved on.

These days Bob has moved out of technology and into motorcycles and golf clubs, so we don’t share as many interests as we once did. We still talk from time to time and I count him among my most valued mentors.

Was your wife nervous about you leaving a steady job to join an entrepreneurial software venture?

“Nervous” probably isn’t the right word, but we both understood it was a big decision. When we started selling my Bible software from home, I commented to her that it would be cool if it got to the point where we could pay the bills with Bible software so I could leave Rockwell. So it was nice to have that opportunity.

In the end it came down to not wanting to look back and say, “I wonder what would’ve happened if I had taken that job at Parsons Technology.” Better to try and fail then not even try.

You hear about people starting successful businesses in their garages. Is that how it went with you?

In a way, yes. QuickVerse started in my spare bedroom and for a few months took over the kitchen. We had a bulletin board by the phone with order forms and UPS delivery time charts. My kids would feed disks into the drive and hit “Enter” to duplicate disks.

Once I went to Parsons Technology full-time, it was the same thing on a bigger scale. We were always bigger and busier than our office space and staffing could support. You had to step around the shipping lady who was sorting packing lists on the floor. The break room doubled as a shrink-wrapping area. And everyone took tech support calls.

I had the unique opportunity to do it all again with Laridian. I left Parsons Technology at the end of 1998 and worked from home writing PocketBible. I had a little 9’ x 12’ home-office off the family room. By 2004, we had leveled that end of the house and I built a 14’ x 26’ office. In 2011 we finally decided to rent space, so I moved out of my home office and have been in a “real” office since then.

Starting a business or venture always has its own set of rewards and challenges. What were some of the challenges that you faced?

I didn’t start Parsons Technology but I was employee number 28 out of what would eventually be over 1200 employees. Working at Parsons Technology was like drinking from a fire hose. We happened to be in an industry (software/tech) that was on fire at exactly that time. This was just before the Web became mainstream, so marketing was via direct mail.

One of our problems was not knowing what we didn’t know. Things moved quickly and everyone took responsibility for anything that needed to be done. So we learned everything about direct marketing by making every single mistake you could make, then trying not to do them again.

For example, when we mailed an offer to our customers, it could cost tens of thousands of dollars. Sometimes we would make money on the offer and sometimes we wouldn’t. We figured out fairly early that we needed to test each offer before mailing to the full list. So we would mail the offer to, say, 1000 people and see how many responded. Based on that, we could project whether or not the offer would make money if we mailed it to a list of 500,000 or a million people. So, for example, if break-even on an offer mailed to 500,000 customers was 2% and we got 25 responses to the test offer, then we could be pretty sure it was going to make money.

We were surprised to find that often we would not get even half the response from the full list that we got when we mailed to the smaller test list. When we finally hired an experienced direct-marketing person, she walked into her first meeting on her first day with a chart showing that we needed to be mailing at least 20,000 pieces to test response rates. Otherwise, the margin of error was just too large to be useful. We started doing that and our direct marketing effectiveness was dramatically improved.

Another problem was growing too fast. When it came time to move out of our rented space, we located some land where we could build and started designing a building that was twice as big as we needed. But before we could get to the point where we had approved the plans, our space needs had doubled and the proposed building was too small. We were constantly dealing with issues like this.

I was more directly involved in the founding of Laridian than in Parsons Technology. The challenges at Laridian have been different.

First, all companies like ours tend to be under-capitalized. We can’t do everything we would like to do because we don’t have the money. We don’t have the money because we can’t do everything we need to do to earn it. And we can’t do everything we need to do because we don’t have the money. So you do what you can with what you have. One of the reasons we worked from home for so long was to avoid the cost of office space, furnishings, and supplies.

Second, our industry changes so rapidly that it is virtually impossible to keep up. Not only are there new mobile platforms, but it can be difficult to predict winners and losers in advance. The iPhone looks like a sure thing today, but when it first came out, it wasn’t obvious that a single phone from a single manufacturer offered on a single cellular network with no way to create native apps would ever become even a second or third-tier player, let alone the leading app platform just a couple years later.

In addition, because technology evolves so quickly, the time you have to reap rewards from your investment in a new platform or new version is very short. Despite this, development must be continuous or you will fall behind within a year or so.

The third major challenge we have is the changing landscape of Christian publishing. Bible software used to be treated like “gravy” for the publishers. That is, they would say, “If we get a few pennies in royalties for electronic versions of our books, great." But now, book publishers see themselves as electronic publishers first and print publishers second. So they expect major revenue from licensing. Publishers who used to accept a 5% royalty are asking for as much as 70% of our revenue now. We have situations where we simply cannot license titles from certain publishers because it is impossible to make any money due to the outrageous royalties. Ironically, we write our biggest royalty checks to publishers with the lowest royalties because we can afford to do so much more with their titles.

What was it like to see QuickVerse become a worldwide Bible program?

Clearly, it was a lot of fun. I don’t think I had time in the moment to think about it much, but I appreciated the fact both that my work was helping people understand the Bible better, and that so many people were able to support their families by doing what they loved, creating and selling Bible software.

I’ve always respected William Tyndale’s story of translating the Bible into English, and love his statement “If God spares my life, ere many years pass, I will cause a boy that drives the plow to know more of the Scriptures than you do." In what ways was your work similar to Tyndale’s?

While other Bible software companies target pastors, scholars, and seminary students, both QuickVerse and PocketBible target the people in the pews. This is intentional. I have always felt that we introduce people to Bible study tools they may not have ever known about otherwise. They get our product to read the Bible and discover they can do searches. Simply being able to search the Bible for words and phrases is more than most people can do with the limited concordance in the back of their printed Bible. Then they discover Strong’s numbers and now they not only have more insight into the meaning of the words behind our English translation, but they also begin to sense the need for understanding the Bible in its historical and cultural setting. This leads them to commentaries and other reference material that expand their knowledge of everything biblical, not just the words in the English version of the text they’re reading.

Many of our customers don’t own a printed Strong’s Concordance or even a good, single-volume commentary. But they may have a whole library of reference materials on their iPhones in PocketBible.

In what ways was it different?

If you’re not careful, you can get lost in the information that a Bible program puts at your fingertips. I cringe when I hear a preacher say, “the word ‘love’ occurs 13 times in this book…”. Bible software makes it easy to know useless facts about the Bible’s 1189 chapters, 31,102 verses, and 12,783 unique words. ;-)

Furthermore, not all of the material that is readily available electronically is as valuable as you might wish. I was at a conference once where a Bible college professor said, “If I get one more paper from an undergrad who quotes from Matthew Henry’s Concise Commentary, I’m going to hurt somebody!”

They say timing is everything, and you certainly benefited from good timing. How is the business climate today different from the 1980’s and 90’s?

Very little of what we learned about direct marketing in the 90’s is relevant today. For example, we spent a lot of time doing demographic and affinity selects on our mailing lists because it costs real money for every single name to which you send snail mail. Today you can send 100,000 emails for the same cost as 100 emails, so why not send your offer to more people and maybe reach people you might otherwise filter out?

In 1992 I could tell you exactly how much I would pay for an ad in your magazine based on the number of male subscribers you had, and depending on whether you were a Christian, computing industry, or general market publication. It’s been ten years since it was possible to make money with a magazine ad, so none of that information is relevant.

Craig with grandson, Peter.

Before the internet, there were plenty of programmers out there with the ability to write a competing Bible software package, but they lacked the funds and marketing experience to actually market and sell their program. This served as a giant entry barrier to new competitors. Today, anyone with a Web browser can download XCode (iOS development environment) or Eclipse (Android) for free, learn how to code by cutting and pasting from the Web, create a Bible app from a wealth of public domain reference material, and submit it to the App Store or Google Play, again for free. You can’t spit without hitting a competitor these days.

Finally, I have programs on my Windows computer that were written in the 90’s and they run just fine today, especially if you’re still running Windows 7 (which a lot of people are). On the other hand, I have iPhones that are less than 5 years old that will not run the latest version of iOS, and will not run the latest version of PocketBible. The pace of operating system and hardware updates is dramatically faster than it was 20 years ago. In the case of Windows, some effort has been made to remain compatible with older programs for longer. But when you look at mobile platforms, apps become un-runnable in just 2-4 years.

The implication of this is that we have to spend a lot more time just modifying already-working code so that it will continue to work as the operating system evolves. That is, we’re not adding new features to take advantage of enhanced capabilities, we’re just fixing everything that breaks between, say, iOS 8 and iOS 9. And as soon as you wring out all the bugs introduced in version X of the operating system, version X.1 comes out.

What was it like, working with Bob?

Suffice to say that he recognized right away the importance of churches to his MoneyCounts business, and immediately saw how QuickVerse could be an “in” for MoneyCounts in that market.

But one shouldn’t conclude that it was only about taking money from churches. Bob was always respectful of my personal beliefs and those of the people who worked for me. He turned down business opportunities that would have been inconsistent with our values and potentially conflict with our Bible software. He never questioned any of the Bibles or books we published. He defended my employees when other employees took offense at the mere presence of Christians in the workplace.

This is what Bob [Parsons] had to say about you:

Our church software division was the brainchild of a man named Craig Rairdin. Craig, on his own, wrote the first QuickVerse program, and did it before joining Parsons Technology. When Craig showed me the program that he had written, I knew instantly that it was well done and would be a hit. Within a few weeks, Craig was our Director of Church Software, and QuickVerse was a Parsons Technology product.

Being a hard worker, Craig soon began hiring additional staff and developing additional Christian products. While Parsons Technology marketed QuickVerse, Craig owned the rights to the product, and after I sold Parsons Technology to Intuit, Craig later sold the rights to QuickVerse to another company.

Was QuickVerse a profitable venture? Did you make a lot of money?

Well, everyone’s idea of “a lot” is different, but QuickVerse was definitely profitable. My original agreement with the company gave me a salary and a share of the profits from my division. When Intuit sold the company to Broderbund in 1997, Broderbund required them to buy me out. That was a seven-figure deal for me, and my interest in working for a large, publicly traded company was rapidly waning, so I didn’t complain.

Stay tuned for part 2 . . . .